Florence Tangka, PhD, Health Economist,

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Cost of Cancer Registration in Limited Resource Settings

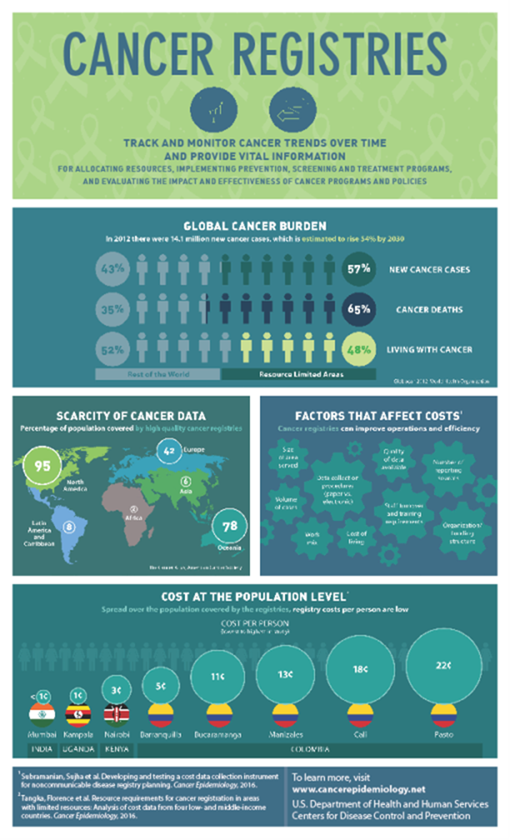

Cancer is a leading cause of illness and deaths worldwide. In 2012 approximately 14.1 million new cancer cases were diagnosed, 8.2 million people died from cancer, and 32.5 million people were living with cancer. More than 50% of the world’s cancer cases and 65% of cancer deaths occur in limited-resource settings, and more than 48% of cancer survivors live in these areas. In the next two decades, new cancer cases are projected to increase by 70% worldwide, mostly in limited-resource settings.

High-quality population-based cancer surveillance data are needed to describe cancer burden, patterns, and outcomes in order to inform cancer prevention, detection and control activities, and evaluate interventions so that the best approaches to ease burden and suffering are adopted. There are large inequalities in the existence, coverage, and quality of cancer surveillance systems across the world, with limited information available in limited-resource settings. For example, the percentage of the population covered by cancer registries ranges from nearly 100% in North America to less than 10% in Asia, Central America, and South America, and roughly 2% in Africa (See Figure 1).

Only one in five countries in limited-resource settings have the data needed to inform cancer control plans. To address this gap, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a specialized agency of World Health Organization (WHO), has initiated the Global Initiative for Cancer Registry Development (GICR) to establish regional resource centers to provide technical support and guidance for the development and improvement of population-based cancer registries around the world.

IARC has developed a framework for planning and implementing population-based cancer registries. However, lack of information about how much registries cost is a major barrier to planning, implementing, and evaluating cancer registration. Yet, investing in high quality surveillance data is crucial so countries can select the best interventions that are both cost effective and most improve health.

CDC, RTI International and others partner developed a tool and used it to collect standardized cost and resource data from 11 registries in Colombia, India, Kenya, Barbados, and Uganda. Findings from this study have been published as a series of manuscripts in Cancer Epidemiology. The study found that partnerships are crucial to developing and sustaining registries. While registries can be expensive, they are less expensive in LMICs and the population level cost is low (less than $0.01 to $0.22 per person). Efficient data collection processes and organizations can cut costs further.

Information on the cost of establishing, improving, maintaining, and expanding cancer registries is essential to ensure adequate funding is available for cancer registration activities. Accurate and reliable costing data is also critical in supporting country-level and regional efforts to plan, implement and evaluate investments in cancer registration.

The abstract below is from the comparative paper published in the Monograph titled “Resource requirements for cancer registration in areas with limited resources: Analysis of cost data from four low- and middle-income countries.”

Resource requirements for cancer registration in areas with limited resources: Analysis of cost data from four low- and middle-income countries (The abstract below is from The International Journal of Cancer Epidemiology, Detection and Prevention)

Abstract

Background

The key aims of this study were to identify sources of support for cancer registry activities, to quantify resource use and estimate costs to operate registries in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) at different stages of development across three continents.

Methods

Using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) International Registry Costing Tool (IntRegCosting Tool), cost and resource use data were collected from eight population-based cancer registries, including one in a low-income country (Uganda [Kampala)]), two in lower to middle-income countries (Kenya [Nairobi] and India [Mumbai]), and five in an upper to middle-income country (Colombia [Pasto, Barranquilla, Bucaramanga, Manizales and Cali cancer registries]).

Results

Host institution contributions accounted for 30%–70% of total investment in cancer registry activities. Cancer registration involves substantial fixed cost and labor. Labor accounts for more than 50% of all expenditures across all registries. The cost per cancer case registered in low-income and lower- middle-income countries ranged from US $3.77 to US $15.62 (United States dollars). In Colombia, an upper to middle-income country, the cost per case registered ranged from US $41.28 to US $113.39. Registries serving large populations (over 15 million inhabitants) had a lower cost per inhabitant (less than US $0.01 in Mumbai, India) than registries serving small populations (under 500,000 inhabitants) [US $0.22] in Pasto, Colombia.

Conclusion

This study estimates the total cost and resources used for cancer registration across several countries in the limited-resource setting, and provides cancer registration stakeholders and registries-with opportunities to identify cost savings and efficiency improvements. Our results suggest that cancer registration involve substantial fixed costs and labor, and that partnership with other institutions is critical for the operation and sustainability of cancer registries in limited resource settings. Although we included registries from a variety of limited-resource areas, information from eight registries in four countries may not be large enough to capture all the potential differences among the registries in limited-resource settings.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and may not represent the official positions of NAACCR.